Background

Galaxy’s Edge and other parks use a Bluetooth beacon system called D-Beacon for a few different purposes, including controlling and activating show sequences (like sound and light effects), presence detection, and navigation within Datapad. Unlike most of the Datapad implementation, the D-Beacon communication is unsurprisingly built into the native application and not abstracted into PlayAPI or the frontend. Deobfuscating the Java output from the (likely) Kotlin-compiled bytecode in my disassembler would be a nightmare. To keep my sanity, I decided it was easier to build a “wardriving”-style sensor platform that I could take on the go and see what the communication between the beacons and the device looks like. I’ve dubbed the endeavour “StarWardriving”.

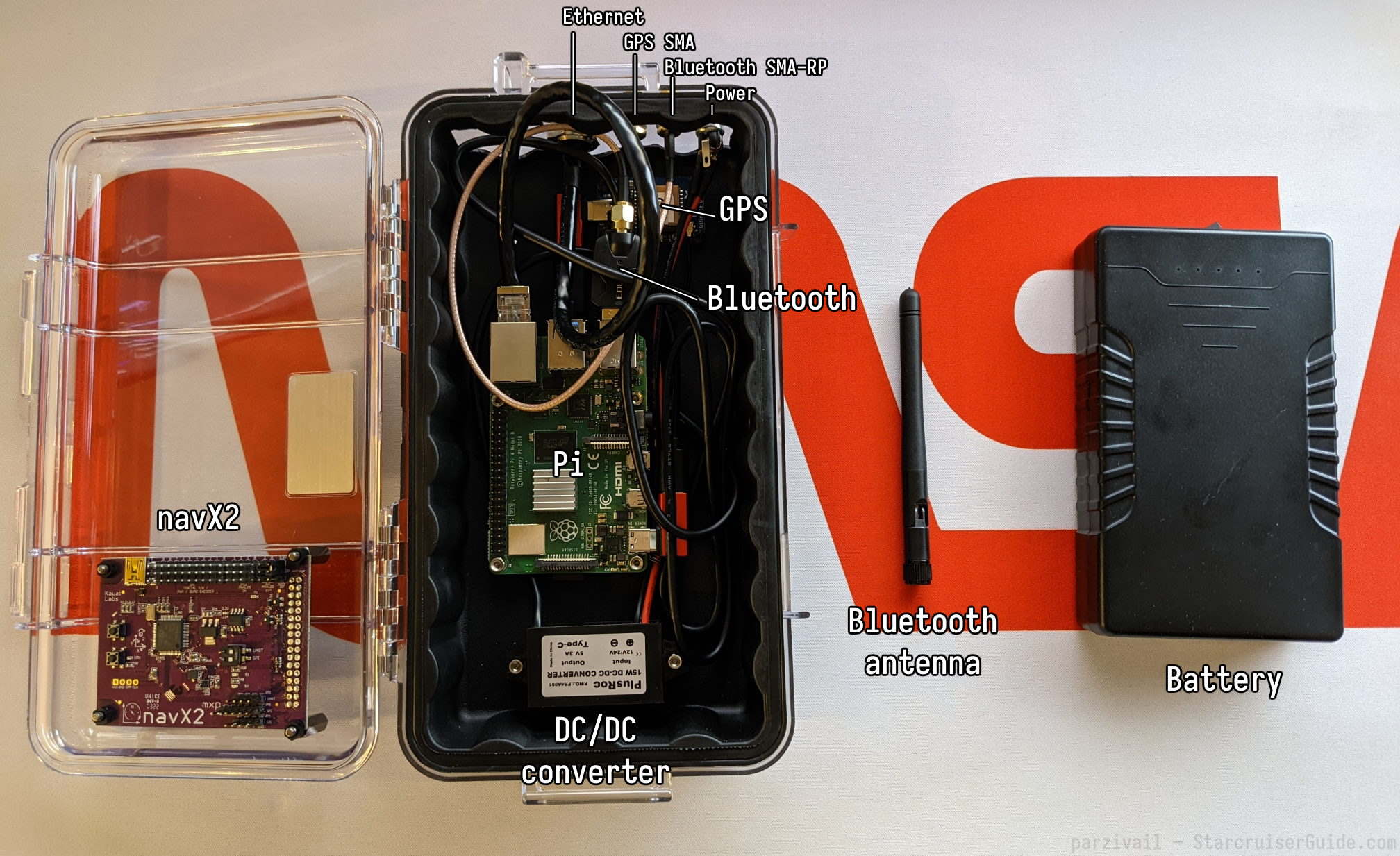

Hardware

- Pelican 1060

- TalentCell 72Wh 12V battery pack

- PlusRoc 12V DC/5V DC USB-C converter

- Raspberry Pi 4

- Adafruit Ultimate GPS (USB-C)

- Kauai Labs navX-MXP 9-axis IMU

- EDUP Bluetooth 5.1 dongle

Case

The entire assembly is housed within a Pelican 1060 Micro Case. All of the boards are attached to the interior with standoffs. Two antenna bulkheads (one SMA connector for GPS, and one SMA-RP for Bluetooth) are fitted to allow external antennas attached to a backpad. An additional 8-pin M12 connector passes Ethernet connection through to the Pi. A DC barrel jack is fitted to bring in 12V power to the DC/DC converter. The case lining largely remains intact in spite of the standoffs, although a section was removed to fit the bulkheads.

Raspberry Pi 4

The heart of the operation is a Raspberry Pi 4 running Raspberry Pi OS Lite (64 bit, kernel 5.15). It has the onboard Bluetooth and Wi-Fi radios disabled to save power, and is set to thermally throttle at 50°C instead of the default 80°C to prevent the case from getting too hot in the Florida summertime. It runs a piece of custom client software called SwgeInspector that continuously logs the data from the GPS, the Bluetooth radio and the IMU. Although the Wi-Fi radio is disabled, it can still communicate over Ethernet, and you can configure your laptop as a DNS server, so you can connect it directly in order to communicate with it.

Battery

The entire setup has been clocked to run for about 20 hours on the 72 Wh battery alone, which puts the power consumption at about 3.6 watts. The capacity should be more than plenty for a day trip to the park.

Sensor Suite

Kauai Labs navX-MXP

The navX-MXP is a 9-DOF sensor fusion board that combines the ST ISM330DHCX accelerometer and gyroscope with the LIS2MDL magnetometer, also from ST. It can achieve as little as 2° of angular drift per day and is an excellent platform for inertial navigation. Here, it’s used to augment the GPS data to provide accurate geolocation and motion data from within the park.

GPS

Adafruit’s GPS module is built around the MTK3333 from MediaTek. It provides up to 10 Hz location updates and consumes fairly little current to boot. Although it has an inbuilt patch antenna, the setup uses an active 3V antenna that will be mounted in the backpack.

It has support for Extended Prediction Orbit (EPO) which theoretically shortens cold boot fix acquisition time by modeling the satellites’ orbits before searching for signals, but the manufacturer has unfortunately discontinued providing EPO ephemeris files. This would have helped the setup quite a bit during cold boots but as long as a cold boot happens with a clear view of the sky, it should find a fix somewhat quickly. There is limited information online about the format and structure of the EPO files, so it may be possible in the future to generate them from data provided by sources like CelesTrak.

Bluetooth

I opted to disable the Pi’s onboard Bluetooth in favor of an external dongle to be able to use an external antenna. The dongle wasn’t immediately supported by kernel 5.15 but I found that the firmware file for the chipset (RTL8761B) just needed an extra U placed in the filename (/lib/firmware/rtl_bt/rtl8761b_fw.bin → /lib/firmware/rtl_bt/rtl8761bu_fw.bin) to denote that the firmware was applicable to USB devices.

Results

I’ll report back after I’ve taken the Inspector to a park for the first time. I expect fix issues with GPS, and I’ve never communicated with Bluetooth beacons before, so I’ll take a laptop on the first trip for the inevitable “production hotfix”.

Images

parzivail

parzivail